Academic integrity is the bedrock of all

scientific and scholarly progress. It's a commitment to honesty, accuracy, and

transparency that ensures the global body of knowledge is trustworthy and

reliable. When this trust is broken through academic misconduct, the

consequences are severe—not just for the individual, but for the entire

research community.

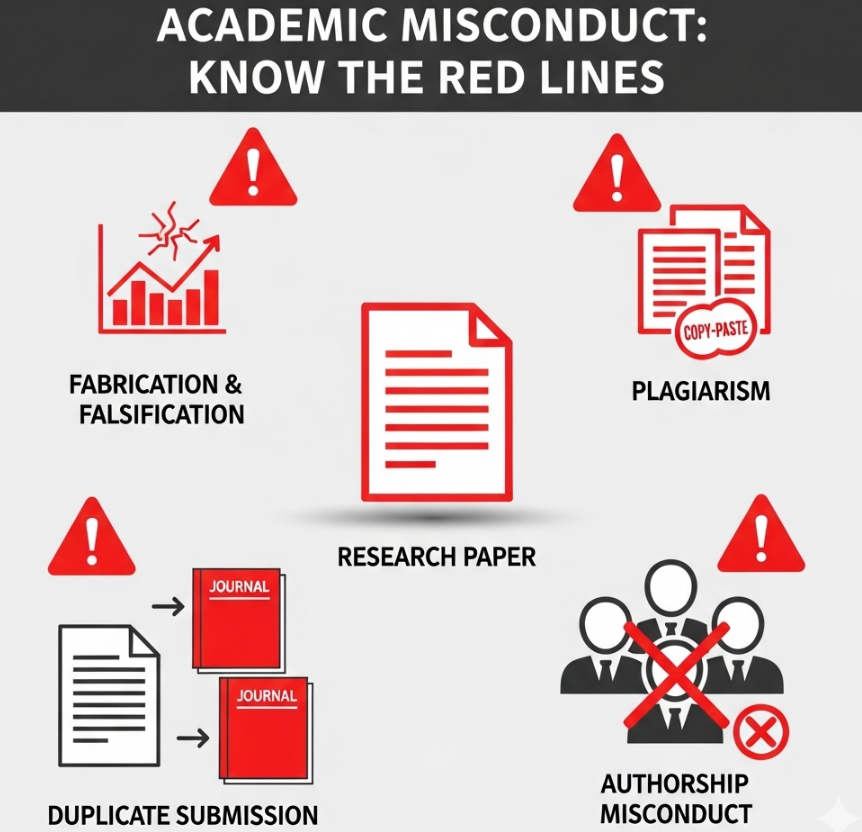

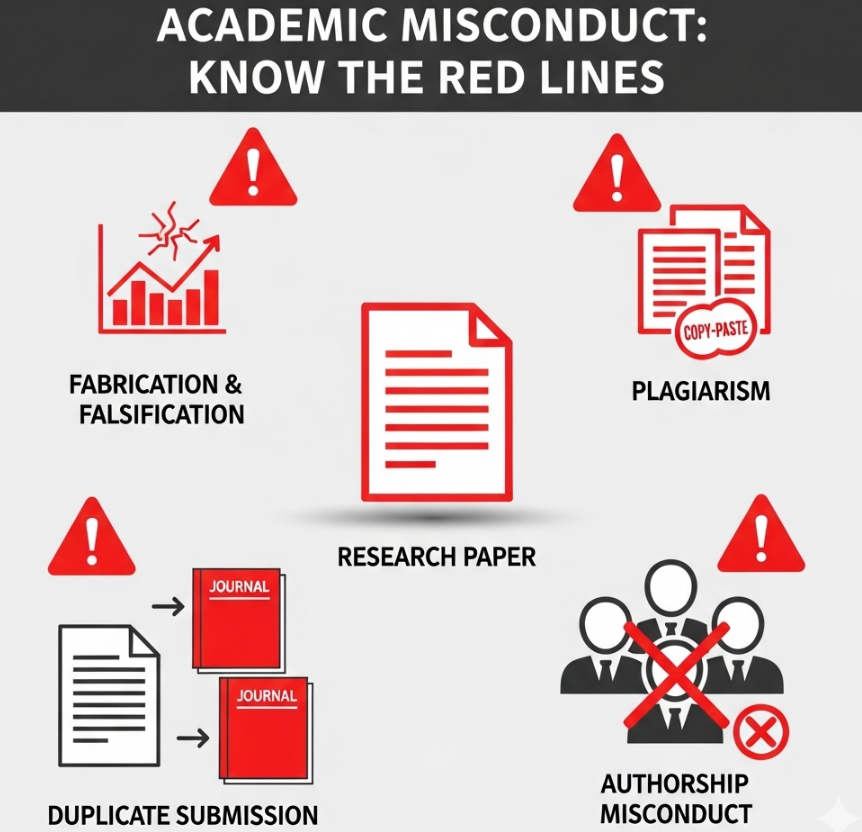

Many forms of misconduct, such as duplicate

submission or data fabrication are considered "academic red lines"

that must never be crossed. This guide clearly defines the most common types of

academic misconduct to help you protect your work, your reputation, and the

integrity of your field.

The Major Forms of Academic Misconduct

These are the most serious offenses in

research and publishing. They are often referred to as FFP (Fabrication,

Falsification, and Plagiarism), but the list extends further.

1. Fabrication: Inventing Data

- What it is: The creation of fake

data, results, or observations. It is, quite simply, making things up and

presenting them as real research.

- Why it's a red line: Fabrication is

the most egregious form of misconduct. It is a deliberate act of deception

that pollutes the scientific record with false information, wasting the

time and resources of other researchers who may try to build upon the

fraudulent work.

- Example: Creating a spreadsheet of

survey results for participants who were never interviewed, or inventing a

series of experimental data points to prove a hypothesis.

2. Falsification: Manipulating Data

- What it is: The alteration,

omission, or manipulation of real research data or results to misrepresent

the findings. Unlike fabrication (which invents data), falsification

starts with real data but distorts it.

- Why it's a red line: It is a

conscious effort to deceive by presenting a skewed or incomplete picture

of the research. It leads to false conclusions and undermines the

scientific process.

- Example: Deleting inconvenient

outlier data points that don't fit a trendline, "cherry-picking"

data that supports a hypothesis while ignoring data that refutes it, or

manipulating images (e.g., selectively cropping a Western blot to hide

unwanted bands).

3. Plagiarism: Using Others' Work

Without Credit

- What it is: The act of taking

someone else's ideas, words, code, or data and presenting them as your own

without proper attribution. This includes "self-plagiarism,"

where you reuse significant portions of your own previously published work

without citing it.

- Why it's a red line: It is

intellectual theft. It violates the fundamental principle of acknowledging

the work of others that your research is built upon.

- Example: Copying a paragraph from

another author's paper and pasting it into your own without using

quotation marks or providing a citation.

4. Duplicate Submission

- What it is: The practice of

submitting the same manuscript to two or more different journals at the

same time.

- Why it's a red line: It unethically

consumes the finite and valuable time of volunteer editors and peer

reviewers at multiple journals for a single piece of work. It can also

lead to duplicate publications, which clutters the academic literature and

can be grounds for retraction.

- Example: Submitting your manuscript

to both Nature Communications and the Journal of the American

Chemical Society simultaneously to see which one accepts it first.

5. Redundant Publication ("Salami

Slicing")

- What it is: The practice of

breaking down a single, substantial study into the smallest possible

"publishable units" to create multiple publications from one set

of data.

- Why it's a red line: While not as

severe as fabrication, it is considered unethical because it artificially

inflates an author's publication list and makes the literature fragmented

and difficult to assess. Each paper must contain a sufficiently novel and

substantial contribution.

- Example: Publishing one paper on

the effect of temperature on a reaction and a second paper on the effect

of pressure from the same experiment, when a single, comprehensive paper

would have been more appropriate.

6. Authorship Misconduct

- What it is: Inappropriately

assigning authorship credit. The author list must accurately reflect who

made significant intellectual contributions to the research.

- Why it's a red line: It

misrepresents who is responsible for the work.

- Examples:

- "Gift" Authorship:

Adding a senior figure or department head to the author list out of

respect, even though they did not contribute, to increase the paper's

chances of acceptance.

- "Ghost" Authorship:

Omitting a deserving junior researcher or technician who made a

significant contribution to the work.

The Consequences of Crossing the Line

Academic misconduct is taken extremely

seriously. The consequences can be career-ending and include:

- Retraction of the publication.

- Notification of the author's institution and funding agencies.

- Loss of funding and academic position.

- Revocation of degrees.

- A permanent ban from publishing in certain journals.

- Irreparable damage to one's professional reputation.

Conclusion

Upholding academic integrity is not a

passive responsibility; it is an active commitment. By understanding these

"red lines" and dedicating yourself to honest, transparent, and

ethical research practices, you contribute to a trustworthy and valuable body

of human knowledge. When in doubt, always seek guidance from a mentor,

supervisor, or your institution's research integrity office.